What's the Problem?

"Untruthful articles can and do influence the way people think, act and vote. Fake news sites aren’t required (or likely) to disclose their falseness the way a satirical news site would, which makes it easier to mistake them for the truth. And while previously only professional news organisations had the means to reach people via papers and TV, now anyone can reach millions through social media, YouTube and the internet... The gates are wide open, and there’s no one guarding them."

Wikitribune (June 2017)

The Internet Society

once observed

that: “the Internet is proving to be one of the most powerful amplifiers of speech ever invented. It offers a global megaphone for voices that might otherwise be heard only feebly, if at all. It invites and facilitates multiple points of view and dialogue in ways unimaginable by traditional, one-way mass media.”

The internet is becoming (to quote Bill Gates) “the town square for the global village of tomorrow.” But as we become ever more dependent on this miracle of human ingenuity, there is growing concern at the internet’s darker side — as a facilitator and amplifier of ‘fake news’, conspiracy theories, cybercrime, hate speech and pornography and malicious disinformation.

Page Content

1 Our Post Truth World

"Stories are more persuasive than logical arguments." Walter Fisher (quoted here)

Thanks to the likes of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump we now live in a ‘post-truth’ world[1] where, for many, facts and opinions have become interchangeable, and experts, evidence and reasoned analysis are routinely scorned and dismissed.

And this has consequences: false promises, 'alternative facts' and 'fake news' confuse and mislead the public; they incite fear, suspicion and distrust, and they undermine social cohesion, democracy and the rule of law. They also limit our ability to tackle serious global issues, like controlling infectious diseases and addressing climate breakdown.

We ignore these imposters at our peril.

2 The Internet

2.1 Can We Fix the Internet?

As

governments around the world have struggled with the coronavirus pandemic, one service has performed with surprising robustness, the Internet. But like so much technology these days we take the Internet for granted — at least until our broadband goes down... And yet problems on and with the system are growing, and there are genuine concerns about privacy and security. If we want to maintain the many services we currently enjoy / rely on, we are going to have get serious about fixing the underlying architecture — and fight off attempts to Balkanise the Web.

Midway through a pandemic — and now war in Ukraine — may not seem a good time to be asking probing questions about the operation of the Internet, but time is not on our side. In November [2020] the International Telecommunications Union

was scheduled to hold a major conference in India, where a delegation from China were due to make proposals for a new IP and if it (and covert lobbying and arm twisting) are successful, it could be a game-changer. The new protocol may well “support faster broadband” (as China claims), but it will also enable authoritarian regimes around the world to have even more control over their citizens.

I've explored six major conundrums surrounding the operation of the Internet in a short paper, 'Can We Fix the Internet?' [click shape] Amongst other things, the paper draws together some of the main developments since 2016 when the Global Commission on Internet Governance

produced a wide-ranging report

which argued that “Internet governance is one of the most pressing global public policy issues of our time”. [Readers may also be interested to read Internet Guru, John Naughton's, paper: ‘The Internet could become a new kind of failed state’ in which he suggests five possible scenarios for the Internet.]

2.2 The Main Elements of the Problem — the Internet 'Thorns'

In his 2019 Richard Dimbleby Lecture

Sir Tim described the combination of factors that led to the web’s creation and the factors that had influenced its development, and (not for the first time) called for ‘a mid-term correction’.

And Sir Tim didn’t hold back in expressing his concern at our collective behaviour online: he reflected on the fact that 10 years ago people would talk enthusiastically about the internet’s ‘roses’ — he singled out Wikipedia, Open Street Map

and the Open Source Movement

as some of the finest 'blooms'; but if asked people's view today, he said, they are just as likely to bring up the internet’s ‘thorns’ — concern over privacy, data rights, security, tracking and advertising.

Sir Tim also lamented the fact that there is a lack of oversight on the web and insufficient transparency and accountability, and that millions of automated systems are today facilitating the spread of hate speech and misinformation. He was also critical of the growing number of governments that routinely block opponents’ content online, or shut down the network altogether when people take to the streets.

2.3 The Internet of Things

The Internet of Things

(and Bodies) is the inter-connection of smart devices — industrial machines, domestic appliances, security cameras, internet routers, wearable or implanted monitors, vehicles, buildings, etc. — which are embedded with software, sensors and actuators which enable them to collect and exchange data via networks and to be operated remotely. Each ‘thing’ is uniquely identifiable through its embedded computing system.

The number of online capable devices has increased rapidly in the last few years: it reached over 8 billion in 2017, and some experts predict that it could reach around 30 billion by 2020, with a global market value in excess of $7 trillion. However, as with all technological advances, there’s a downside — indeed, the risks are considerable, not least invasion of privacy, the potential for political manipulation / social control, and fraud on an industrial-scale.

3 Misinformation & Conspiracy Theories

Misinformation can include many things: ‘fake news’, ‘alternative facts’, lies peddled as facts / facts dismissed as lies, doctored photos, deepfake videos and madcap conspiracy theories. I’ve stopped referring to these collectively as ‘bad information’ because the term ‘misinformation’ is more widely used / understood and there is the potential for confusion. Moreover, the term ‘bad information’ might reasonably be taken to include information that, whilst factually accurate, is distasteful or offensive. [2] Technically:

•

misinformation

is information that is false, but not created with the intention of causing harm;

• disinformation is information that is false and deliberately created to cause harm.

• disinformation is information that is false and deliberately created to cause harm.

Related terms we also need to consider include:

• conspiracy theories

— beliefs that some effect or event either did not happen in the way reported, or that some powerful, covert and malevolent organization was responsible;

• mal-information — information that is private or confidential which has been made public in order to inflict harm (e.g. ‘doxing’)[3]; and

• weaponized narrative

— an attack that seeks to undermine an opponent’s civilization, identity and will. [4]

There is further discussion of these different forms of misinformation (with examples) on a separate page.

Phrases such as ‘fake news’ and ‘junk news’ are rather vague and have fallen out of favour with journalists and news professionals, and I try to avoid them where I can — along with the term ‘alternative facts’, which is more a statement about the user

than a clear class of misinformation. [5]

3.1 'Fake News' & Fraud

In mid-2016 Buzzfeed's media editor, Craig Silverman, noticed a strange stream of often fanciful stories that seemed to originate in one small town in Eastern European town, Veles in Macedonia. Silverman and a colleague subsequently identified over 140 fake news websites which were putting out huge numbers of stories on Facebook. 'Fake News' is real and has turned out to be extraordinarily 'sticky'. Later in 2016 the term ‘fake news’ made its first appearance in the mainstream media; it was picked up by Trump; and the rest is history...

If you've ever wondered what’s the difference between 'fake' and 'fraud': 'fake' is something which is not genuine or is misrepresented, whilst 'fraud' is any act of deception carried out for the purpose of unfair, undeserved and / or unlawful gain. [6]

Fake news produced and circulated for amusement or to make money (via clickbait) may not technically be illegal; but if it is done with the intention of deceiving people, it most definitely is. [Cybercrime is discussed on a separate page.]

3.2 Misinformation about Covid-19

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to gather pace, a slew of health advice has been doing the rounds on social media, ranging from useless but relatively harmless, to downright dangerous. Russia is also reported

to be “deploying coronavirus disinformation to sow panic in West”, and cyber-criminals have been having a field day targeting a wide range of health-related industries with phishing emails, some laced with ransomware.

The World Health Organization

says that the Covid-19 outbreak had been accompanied by an 'infodemic' (an abundance of information, some accurate, some not); and WHO is concerned that misinformation surging across digital channels is impeding the public health response and stirring unrest.

3.3 Fake News Around the World

This page

highlights reports, articles and videos dealing with the impact of rumour, misinformation and downright lies on social media, particularly in low-income countries. In many rural areas Facebook

has become the

main source of news and information for many people, and there has been a growing number of incidents reported in which the platform has been used to tarnish or blacken a politician's reputation, or to foster racial or inter-religious hatred, sometimes with grotesque results.

False information is a potentially serious issue in the Charity Sector: it can undermine public trust, destroy years of careful, on-the-ground work in the community, and sometimes put the lives of development workers at risk.

3.4 Fake News in History

'Fake news' in the sense of propaganda* has been with us a long time. The Prologue to Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 2 (written ~ 1599) is spoken by a figure dressed as Rumour.

Rumour is the personification of hearsay — stories that circulate without any confirmation or certainty. He is "painted full of tongues" and there to “open men’s ears” and “stuff them full of lies.” During the Renaissance, Rumour was often associated with warfare — in this image (from Cartari's Images Deorum, 1582) he is pictured blowing a trumpet as Mars, the God of War, follows behind.

Some educationalists argue that the foundation for much of today's 'fake news' can be laid at the door of fake history, which as one proponent of this view argues, "promotes false narratives, twists the facts, or omits certain key facts altogether."

* The term 'propaganda' has its origins in the Holy See (as explianed in this section)...

3.5 Ghostwriter Influence Campaigns

Hackers can break into real news websites and post fake stories. One ‘Ghostwriter Campaign’, ongoing since 2017, is aimed at stirring up anti-NATO sentiment in Eastern Europe. One report

(by Mandiant Threat Intelligence; Jul 2020) has “moderate confidence” that ghostwriters are part of “a broad influence campaign aligned with Russian security interests.” Operations have primarily targeted audiences in Lithuania, Latvia and Poland with narratives critical of NATO presence in the region and occasionally leveraging other themes (such as anti-US & Covid-19-related narratives) as part of this broader anti-NATO agenda.

3.6 How DisInfo is Used to Damage Brands

A handbook from Yonder

explains what brands can do to protect their relationships with consumers, and prevent damage to their reputation. Here's an extract:

"When inaccurate info spreads online, brands can lose control of their image and story. Influential, agenda-driven groups online don’t always target brands but use them as vehicles for disinfo and as platforms to spread their messages far and wide.

False claims and hoaxes — from fake coupons to damaging stories — can lead to loss of customer trust (often unrecoverable) due to the challenges involved in correcting narratives spread by disinformation campaigns.

Disinformation campaigns can damage brand reputation and lead to revenue loss. This can range from a drop in the value of company stock to decreases in sales due to boycotts and loss of customer loyalty."

3.7 Deepfakes

Deepfake

is a technique for synthesising videos using artificial intelligence. It involves combining and superimposing existing images and videos onto other images / videos . The term is usually applied to:

- Face-swapping — where someone's face is superimposed on someone else’s (here Nicholas Cage for Sean Connery playing Bond); and

- Video Dialogue Replacement

— a technique that combines audio with manipulated video to make it look like the person is actually saying words they never said. However, it might also be used in relation to:

- Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) — special effects used in block busters. One of the most recent examples of this is the de-aging technology used in ‘The Irishman’.

3.8 Conspiracy Theories

A conspiracy theory is a belief that some effect, event or trend either did not happen in the way reported or as commonly understood, or that some powerful, covert and usually malevolent organization was responsible, or it didn't happen at all. Some conspiracy theories are true, but many turn out to be false, and these have become a major problem for 21st century society: “They hurt society by distracting from the very real problems of corruption and decreasing genuine participation in democracy” and "they hurt individuals by affecting their life choices, like money, health, and social interactions."

3.9 Bad Science & Pseudoscience

Bad science includes real science done badly or with fraudulent intent.

The main forms of misconduct in scientific research are: fabrication

— making up results (sometimes referred to as ‘dry-labbing’); falsification

— manipulating research materials, equipment or processes or changing or omitting data / results such that the research record is corrupted; and plagiarism

— appropriating other people's ideas, results or words without giving appropriate credit.

Pseudoscience is the term applied to statements, beliefs or practices that are claimed to be factually-based but which are not supported by scientific evidence. The whole field is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims, or a lack of openness to scientific evaluation or rigorous attempts at refutation.

3.10 Fake Fact-Checking Sites

In March 2018 RT (formerly Russia Today) set up FakeCheck

to "debunk fakes that are extensively distributed across the mainstream media." The development has not been universally welcomed. Indeed it met with sarcasm from some in the West. RT has itself been accused of spreading misinformation (a position it vigorously denies).

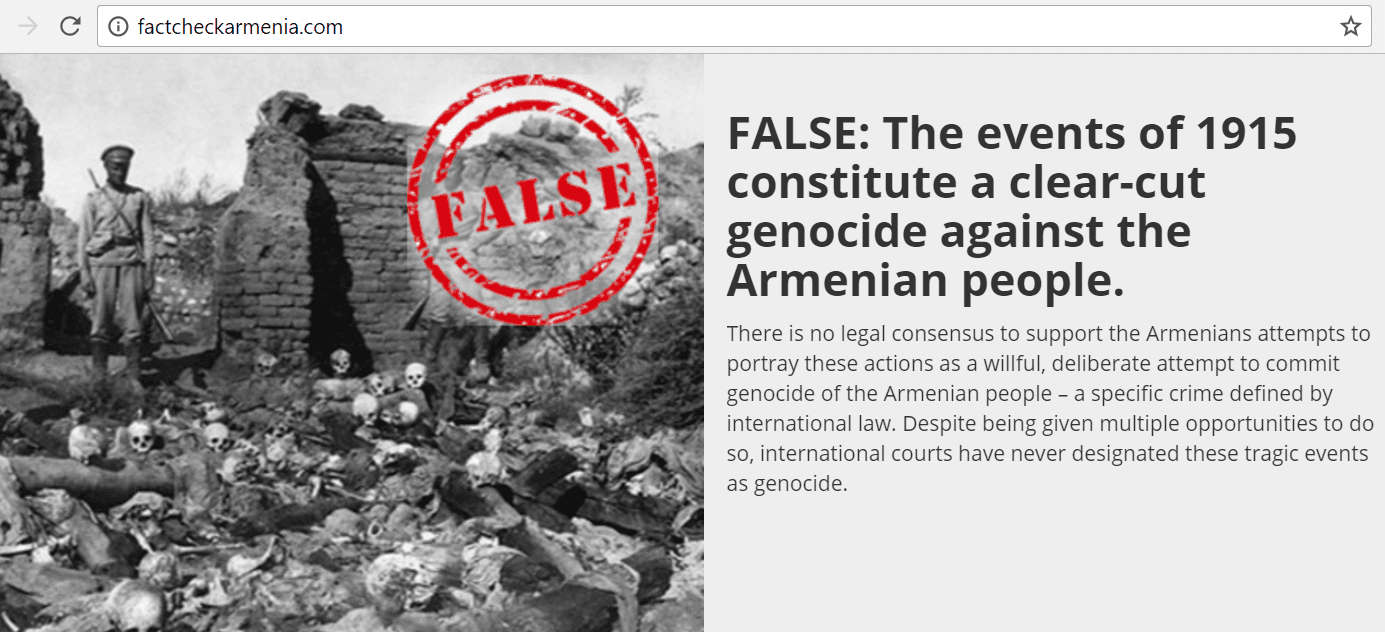

Similar concerns have been raised about Turkey's entry into fact-checking. This image is a screen-dump from FactCheckArmenia.com

website which has hidden its sponsorship. Fake Fact-Checking websites

are not currently a major issue, but they could become so.

4 Social Media & Media Bias

4.1 Grabbing Our Attention

Advertising agencies and internet companies use various psychological tricks to grab our attention and then keep us engaged on their apps or websites. There are, of course, codes of conduct, which they should follow, but these can be hard to police on the internet. This page

provides a layperson's overview of some of the techniques that are being used and summarises the ways in which we react to new information, images and ideas.

4.2 Media Bias

Wikipedia

defines media bias

as “the bias or perceived bias of journalists and news producers within the mass media in the selection of events and stories that are reported and how they are covered.”

The term "implies a pervasive or widespread bias contravening the standards of journalism, rather than the perspective of an individual journalist or article.” It notes that “the direction and degree of media bias in various countries is widely disputed,” and that practical limitations to media neutrality include “the inability of journalists to report all available stories and facts, and the requirement that selected facts be linked into a coherent narrative. Government influence, including overt and covert censorship, biases the media in some countries, for example North Korea and Myanmar.”

4.3 Human Rights & Disinformation

Disinformation is a human rights issue

because it can cause harm to a range of human rights, including:

• the right to free and fair elections;

• the right to health

• the right to freedom from unlawful attacks upon one’s honour and reputation

• the right to free and fair elections;

• the right to health

• the right to freedom from unlawful attacks upon one’s honour and reputation

• the right to non-discrimination.

Disinformation needs to be seen, not just as a type of content, but as a type of deceptive behaviour, what people are calling 'viral deception'.

4.4 The Human Cost of Content Moderation

The human cost of viewing disturbing content under pressure is considerable, as Chris Gray discovered. He developed PTSD after moderating content for 6 months in Facebook's Dublin office. [More about Chris' story here.] Facebook

has ‘Deletion Centres’ in a number of countries and a 35,000-strong army of Content Moderators. [It is working to increase its use of artificial intelligence to remove harmful content, but it and the other social media platforms still have a long way to go.]

5 Truth & Public Trust

5.1 Truth

We consider a statement to be ‘true’ when it conforms to our understanding of reality, in other words it matches up with the way we see the world, and facts or statements can be verified beyond reasonable doubt. This is ‘observed truth’, and what we most commonly mean when we say something is ‘true’. ‘Scientific’ and ‘mathematical’ truth are special kinds of objective truth, where every care is taken to eliminate bias on the part of the observer.

Subjective truth is a rather different animal: it is private and personal and includes belief — constructs that are held to be true but which may not be justified or supported by factual evidence. Within this category we have: ‘moral truth’, ‘sacred truth’, and ‘emotional truth’.

For further analysis of truth see here.

5.2 Ministry of Truth

In George Orwell’s dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, there is a ‘Ministry of Truth’ which is responsible for propaganda, historical revisionism, culture and entertainment. Of course, as with the other ministries in ‘Oceania’, the name is a misnomer as the Ministry’s main purpose is misinformation and falsifying historical events so that they agree with Big Brother.

If Big Brother makes a prediction that turns out to be wrong, the employees of the Ministry correct the record to make it 'accurate' — the intention is to maintain the illusion that the Party is right / absolute. The Party cannot ever seem to change its mind or make a mistake as that would imply weakness; so the Ministry controls the news media by changing history, and changing words in articles about current and past events so that Big Brother and his government are always seen in a good light. Sound familiar?

5.3 Collapse of Public Trust

6 New & Developing Threats

Society is facing a range of new threats derive mainly from advances in Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things / Bodies and a rise in state surveillance. Tackling such threats without degrading internet services and compromising our privacy, security and freedom of expression is proving highly problematic, not least because of the multiplicity of agencies and organisations involved in trying to regulate and police online content and the poor coordination between them; and very real concerns about unintended consequences.

7 In Summary

The Internet — which was first used as a way for scientists to share research findings — has developed into an extraordinary tool for research, education, commerce, entertainment and social intercourse, but it is today being used increasingly to disseminate tittle-tattle, rumour, uninformed opinion, negative advertising, conspiracy theories, and worse, hate mail, revenge porn and extremist propaganda — and there's even worse on the Dark / Deep Web. [7]

This development has serious potential consequences for the quality of public discourse, and for social cohesion and democratic government. Indeed, the stakes could not be higher. This explains why so much effort is now going into tackling fake news and malign propaganda. We discuss this on a separate page, where we have also provided information on what concerned citizens and groups can themselves do.

Is there anything wrong with this page?

If you would like to comment on the content, style, or the choice or use of material on this page, please use the contact form. Thank you!

Notes

2 Note that The Royal Society

recently defined

‘scientific misinformation’ as “information which is presented as factually true but directly counters, or is refuted by, established scientific consensus. This usage includes concepts such as ‘disinformation’ which relates to the deliberate sharing of misinformation content.”

3

Doxing or doxxing is “the act of publicly revealing previously private personal information about an individual or organization, usually via the internet. Methods employed to acquire such information include searching publicly available databases and social media websites, hacking, social engineering and, through websites such as Grabify (which reveals IP addresses through a fake link.” [Wikipedia]

4

“By generating confusion, complexity, and political and social schisms, [weaponized narrative] confounds response on the part of the defender.” It has been likened

to “a firehose of narrative attacks [that] gives the targeted populace little time to process and evaluate. It is cognitively disorienting and confusing — especially if the opponents barely realize what’s hitting them. Opportunities abound for emotional manipulation undermining the opponent’s will to resist... many different types of adversaries have found weaponized narratives [effective, from Russia’s meddling in election of Western democracies and Islamic States grisly propaganda; other] recent targets have included Ukraine, Brexit, NATO, the Baltics, and even the Pope."

5

‘Alternative facts’ was a phrase used by Kellyanne Conway during a Meet the Press interview on 22 Jan 2017, in which she defended White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer's false statement about the attendance numbers at the President’s inauguration.

6 The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

defines fraud as “the intentional false representation or concealment of a material fact for the purpose of inducing another to act upon it to his or her injury.”

7

The Dark Web is the World Wide Web content that exists on darknets (overlay networks which use the Internet but require specific software, configurations or authorization to access). It consists of hundreds of thousands of websites that use anonymity tools like Tor and I2P to hide their IP address. The Dark Web forms a small part of the Deep Web (that part of the Web not indexed by search engines). Users of the Dark Web refer to the regular web as Clearnet due to its unencrypted nature. The Tor Dark Web may be referred to as onionland, a reference to the network's top level domain suffix .onion and the traffic anonymization technique of onion routing. [Wikipedia

edited] This short video

provides an excellent description.

1