People Fighting Fake

“How much more easily will a lie be able to spread when there’s video ‘evidence’

to back it up? Fake news? We’ve barely got started.” Helen Lewis

to back it up? Fake news? We’ve barely got started.” Helen Lewis

This page

summarises some of the ways in which governments, business, the media and civil society are trying to tackle the threat posed by misinformation, half-truths, lies and malicious propaganda. The main focus is on efforts in the UK, but examples from other countries are also included, along with comments on the work of international agencies.[1]

The fight against bad information is being conducted on many levels and by a range of different organisations and individuals acting on their own or collaborating with others.

Some broad categories are shown in the diagram. These include: educational establishments and the mainstream media promoting media literacy, critical thinking and quality journalism; NGOs and consultancies engaged in data analysis, website labelling, fact-checking, and forging tools to detect fraud or content tampering; national agencies responisble for governance, legislation and security, and international bodies concerned with regulation, cybersecurity, and drafting international treaties and conventions. [2]

Page Contents

Subheadings:

1 Schools & Colleges

Schools also need to teach children how their data is collected and used and what they can do to take control of their data footprint. This should cover information shared online, information gleaned from connected devices in the home, and information gathered elsewhere through public and commercial services. There is a growing repository of educational material on the web dealing with concepts such as ‘truth’ and the distinction between facts, opinion, evidence and argument ─ see Resources.

Wherever possible critical thinking should include a grounding in basic philosophy which can help people, especially young people, think for themselves, challenge misinformation and resist attempts at indoctrination.[4] We like one college prospectus

which says it helps students “navigate the bullshit-rich modern environment” and “combat bullshit with effective analysis and argument.”

2 Individuals & NGOs

A wide spectrum of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and committed individuals are today fighting fake by: evaluating websites for factual accuracy and bias; assessing whether politicians' comments or statements are accurate and images are genuine; looking for coordinated inauthentic behaviour on social media; promoting quality journalism; and or working to raise public awareness of the threat.

Other NGOs are: tackling hate speech; promoting online safety; and fighting for people’s privacy and rights. And some do this very effectively with the proverbial 'paint brush' or 'pen', via cartoons or satire.

2.1 Cartoonists & Satirists

In June 2020 The Washington Post

reckoned that Donald Trump had uttered around 20,000 ‘misleading claims’ since his inauguration ─ that’s an average of almost 15 a day. The EU vs DisInfo

accuses Vladimir Putin and Kremlin proxies of disseminating over 9,000 ‘fake news’ stories since 2015 when the Unit was set up ─ ie around 5 porkies

a day.

Cartoonists and satirists can be particularly effective at holding such sociopaths and dictators to account for their policies, actions, promises or threats. There's nothing that powerful people like less than being the butt end of jokes.[5]

2.2 Writers & Bloggers

Many websites and bloggers provide useful advice or information to counter ‘fake news’, conspiracy theories and disinformation.

The website featured here is Debunking Denialism, one of the longest-running: it was set up in 2010 to "oppose pseudo-science and quackery with reason and evidence". Hundreds of books and reports have also been published since 2016 when 'fake news' first hit the headlines. McNamee’s book 'Zucked: waking up to the Facebook catastrophe' is a good example ─ McNamee was an early mentor to CEO Zuckerberg/investor in Facebook: he wrote the book after Zuckerberg rejected his concerns.

You will find many more titles ─ and references to interesting websites ─ on the Resources Page.

2.3 Public Education, Civil Rights & Internet Safety

Many of the NGOs fighting fake are involved in:

• public education or training

• tackling hate speech

• promoting online safety (especially for children)• protecting people’s privacy and rights.

The photo is of a workshop for local journalists on how to deal with disinformation [London, Oct 2019]. It was organised and run by FirstDraft.

Here are some representative examples of organisations working in different area to tackle hate speech and misinformation and raise awareness of online dangers:

• #JaGarHar

[#IAmHere] in Sweden ─ tackling online hate speech

• Innocence in Danger

─ protecting children and young people from explicit material online, and from grooming and other forms of exploitation [the image below if one of theirs]

• Internet Watch Foundation

─ operates a hotline for the public to report potentially criminal content online; also works with the police to issue ‘takedown notices’ to Internet Service Providers, and has been active in the development of website rating systems [6]

• DeSmogUK

─ describes itself as "a go-to source for accurate, fact-based information regarding misinformation campaigns on climate science in the UK".

Four other organisations working in the UK on online safety and rights are worth a mention:

Examples of NGOs working internationally to actively defend civil rights / internet freedom include:

• Electronic Frontier Foundation

─ provides funds for legal defence in court, presents amicus curiae

briefs, and challenges potential legislation that it believes would infringe on personal liberties and fair use;

• Global Witness

─ helps challenge censorship; and

• World Wide Web Foundation

─ US-based international non-profit focused on increasing global access to the Web

while ensuring that it is a "safe and empowering tool that people can use freely and fully to improve their lives."

Last but not least, there are Special Interest Groups, like the Union of Concerned Scientists

(in the US) and Sense About Science

(in the UK), which challenge the misrepresentation of science and scientific evidence in public life.

2.4 Holding Government & Political Parties to Account

Virtally all of the above NGOs are actively lobbying for a cause. And there are many others...

One featured here is The Coalition for Reform in Political Advertising

which believes that "the rules designed to safeguard against the spread of disinformation and promote healthy political debate haven’t kept up with the pace of new communication technologies." In Dec 2019 the Coalition published 'Illegal, Indecent, Dishonest and Untruthful, How Political Advertising In The 2019 General Election Let Us Down.' One voter who got in touch with The Coalition about a seriously misleading election campaign leaflet said simply: “I don’t know who to complain to, or how to complain.”

2.5 What We Can Do

There's a separate page

devoted to things we personally can do to help fight fake. It includes a list of (free) specialist newsletters

on mis / disinformation produced by NGOs and consultancies.

3 Think Tanks, Consultants & The Media

Think tanks, consultancies and the mainstream media are also actively involved in a number of the above issues as well as monitoring content, data analysis and fact-checking. Here are a few observations.

3.1 Data Gatherers & Analysts

Some digital market intelligence companies track the development of social media and seek to understand who’s using it and how. They are an important source of intelligence eg about suspicious / inauthentic behaviour online (which could be due to bots). Most analysts appear to be commercial companies like Netcraft, SimilarWeb, Sysomos, Technorati

and Vuelio

(and there are many more...) In the non-profit sector there are initiatives like Amnesty International’s Citizen Evidence Hub. One particularly worth mentioning is Graphika, which "supports social networks like Facebook in the ongoing fight for authenticity online by identifying bots and coordinated campaigns at scale." Graphika

researches the tricks bad actors play and is a prolific reporter — the study shown here is concerned with pro-Chinese spam.

3.2 Website Evaluation

A good example of an organisation involved in evaluating websites for factual accuracy/bias is Newsguard, which describes itself as an "Internet Trust Tool". Newsguard

provides 'trust ratings' on more than 4,500 news websites "that account for 95% of online engagement with news" and

displays ratings icons next to links on all the major search engines and social media platforms. It uses five flags:

• green ─ news & information sites that follow basic standards of accuracy and accountability.• red ─ news and information sites do not (like RT's rating [Russia Today], shown here).

• orange ─ sites primarily host user-generated content

• purple ─ humour or satire that mimic real news

• grey ─ not yet rated by Newsguard team

Another website evaluator is the Global Disinformation Index

(GDI) which aims to "disrupt, defund and down-rank disinformation sites." It works with governments, business and civil society and operates on three core principles: neutrality, independence and transparency. Its mission is "to catalyse change within the tech industry to disrupt the incentives to create and disseminate disinformation online."

3.3 Fact Checkers & Myth Busters

Around 200 independent fact checkers are today operating in over 50 countries, ~60 registered with the International Fact Checking Network

[IFCN]. One of the oldest is Snopes.com

which investigate suspect websites, news stories and politician's claims or comments. Poynter, which oversees the IFCN, operates a strict Code of Principles

for members and organises an annual 'Global Fact Check' meetup ─ see Pulldown below. A list of fact checkers around the world can be found on Wikipedia.[7] Some of the main UK Fact Check sites are listed in the Pulldown below.

Then there are others, like Storyful’s Open Newsroom, that focus on bringing together journalists and other news professionals to investigate big news stories in real-time to debunk, check, clarify, credit and source material.[8] Images can also be 'fact checked' for signs of tampering or inauthenticity (see tools for spotting fake).

Progress with automatic take-down services for fake websites looks promising — one report suggested that take-down speeds have been reduced to around an hour (from over 20). However, more is required because the longer suspect sites are operating, the more people they can fool and the more ‘business’ they can generate. [9]

3.4 Mainstream / Online Media & Encyclopaedias

A wide spectrum of organisations are working to promoting quality journalism. They include:

• the mainstream media — broadcasters (like the BBC & CNN) and the quality press (The Guardian, New York Times, Washington Post, etc.);

• online-only media (like YahooNews

& The Huffington Post);

• online encyclopaedias (like Wikipedia); and

• specialist bodies like the Ethical Journalism Network

(in the UK) and Columbia Journalism Review

and Neiman

(in the US).

The BBC

has been particularly active on disinformation. In September 2019 it linked up with tech firms to: create an early warning system alerting others to specific disinformation. It also set up a joint online media education campaign; and co-operates with other interested parties on voter education and shared learning, especially around elections. There's a broader discussion of the media — and the tricky question of media bias and government interference / censorship — on this page. (This includes a discussion and explanation of the adjacent chart.)

3.5 Professional Representative Bodies

& Research Integrity Offices

Associations and trade bodies that represent scientists, journalists, librarians and other information professionals are keen to maintain standards in their sector and moderate the behaviour of their members. These include: an Internet Service Providers Association

and an International Association for Information & Data Quality.

This is in addition to the Internet Society

(which is concerned primarily with “ensuring that the Internet stays open, transparent and defined by you”).

The UK has a Research Integrity Office

which promotes "the good governance, management and conduct of academic, scientific and medical research; and shares good practice on how to address poor practice, misconduct and unethical behaviour." [10]

3.6 Specialist Research & Advice

There are also a number of Think Tanks and British university units / departments that have a special interest in the area of quality journalism and disinformation [too many to list]. Prominent examples (in theUK) include:

• Centre for Investigative Journalism

[Goldsmiths, University of London]

• Centre for the Analysis of Social Media

[DEMOS, which works with the University of Sussex]

• Digital Society Initiative

[Chatham House]

• CREST

[Centre for Research & Evidence on Security Threats; Lancaster University]

• Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism

[University of Oxford]

There are also two networks of experts offering help and advice on mis/disinformation and conspiracy theories:

• Global Experts on Debunking of Misinformation

• DisinfoPortal.org

This is in addition to the Atlantic Council's network of 'Digital Sherlocks' (see Section 6 below).

• DisinfoPortal.org

This is in addition to the Atlantic Council's network of 'Digital Sherlocks' (see Section 6 below).

4 Tech Giants

& Software Companies

Big Tech includes powerful business interests concerned with social media, internet search engines, internet service providers, and machine learning/artificial intelligence (to name but a few of their many other interests / pursuits!) They have been concerned about fake accounts and hateful, extremist or illegal material on their systems for some years.

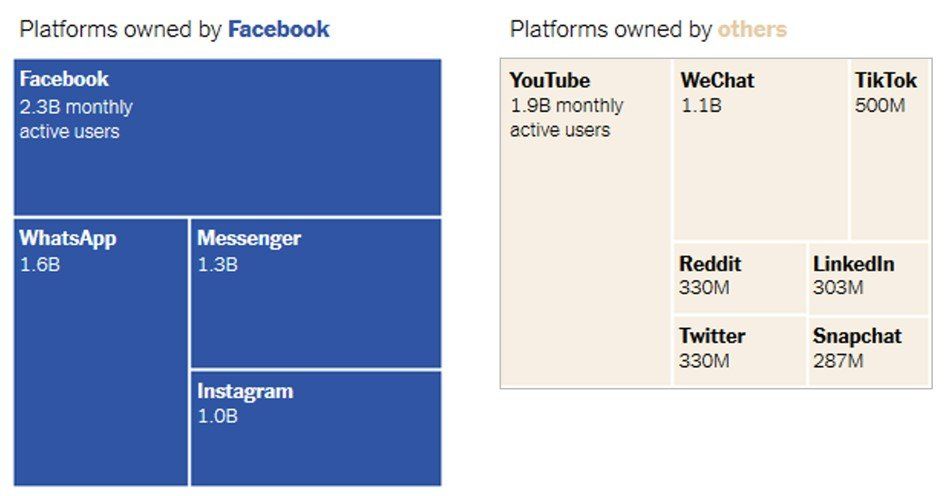

Facebook, which is by far the biggest operator (as the graphs below demonstrate) has

‘Deletion Centres’ in a number of countries and a 35,000-strong army of Content Moderators. In 2019 it also set up a ‘War Room’ to respond in real time to attacks / disinformation campaigns, expecially around election times. It is also increasing its use of AI to remove harmful content and routinely deletes literally millions of fake accounts — as do all of the major platforms. For example,

Twitter

suspended over 70 million accounts in just two months in 2018 (and many more since) in its efforts to clamp down on disinformation; and YouTube

(which is owned by Google) has also introduced measures to stem the spread of conspiracy theory videos and fake news on its platform, including inserting context from trustworthy sources into search results for hot topics.

The graphic below shows thotal number of active users on social media in 2020, and those in the UK.

How successful the Techn Giants are at ridding their platforms of bad actors, hate speech and disinformation is an interesting question (see Section 7).

Website Builders

A related issue is the responsibility of website builders to monitor what their clients upload onto the websites on their platforms. One specialist in the field, Website Planet, tested

seven website builders and found most of them wanting. It uploaded websites full of fake news about COVID-19 onto their platforms. Only 2 took down the fake news sites immediately; others said they would 'look into it', or simply didn't respond.

5 Politicians, Lawyers & Regulators

Politicians have a very important responsibility when it comes to tackling many of the problems associated with 'fake news' and disinformation.

5.1 Regulators & Prosecutors in the UK

In the UK, the Digital, Culture, Media & Sports Select Committee

[DCM&S] produced an excellent report on 'Disinformation and 'Fake News'' (in Feb 2019) after taking evidence for over a year. Two of its main proposed were that: social media platforms be held responsible for 'harmful' content on their services; and

technology companies be taxed to fund a public information campaign (to help people identify ‘fake news’ and pay for increased regulation).

These and some other recommendations are discussed on The Battle for Truth Page.

Various agencies are responsible inter alia

for regulating service providers and non-governmental organisations, and maintaining the law and standards of public decency, intellectual property rights, etc. They include (in the UK) such bodies as: the Information Commissioner's Office

(ICO), the Health & Safety Executive, the Charity Commission, Advertising Standards Authority,

and the Crown Prosecution Service

(CPS).

The ICO, for example, was set up to uphold information rights in the public interest, promote openness by public bodies and data privacy for individuals. If someone has posted wrong or malicious information about someone online, they can report it to the Commissioner, who may in turn take it up with the CPS (see separate page). The role and responsibility of some of the other bodies is also discussed here.

5.2 Anti-Disinformation Initiatives Around the World

In Aug 2019 the Oxford Technology & Election Commission

published 'A Report of Anti-Disinformation Initiatives' around the world.[11] It was prepared by BBC Monitoring’s specialist Disinformation Team

and "investigates fake news landscapes around the world and analyses a range of measures adopted by governments to combat disinformation. The analysis provides geopolitical context with timely, relevant examples from 19 countries in four continents (with a particular focus on European nations). The team also reports on the European Union because of its size, power, and influence."

In relation to oversight and regulation it is worth noting that an International Grand Committee on Disinformation and ‘Fake News’

was formed in Nov. 2018 after Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg repeatedly refused to give evidence to the Parliamentary Enquiry into Disinformation and ‘Fake News’.

The Committee is comprised of parliamentarians from Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, France, Ireland, Latvia, Singapore, and members of the UK’s DCM&S Committee.

6 National Security & International Agencies

All Western intelligence agencies are responding to the deluge of disinformation generated by domestic bad actors and hostile foreign governments and their proxies. Information on some of these agencies is provided below.

6.1 The United Kingdom

The main agencies in the UK working to neutralise malefactors and mischief-makers and protect vital infrastructure from cyberattack are GCHQ

[shown], MI6, MI5

and the National Cyber Security Centre. Little is known about the work of these bodies however with respect to offensive actions it appears that the Government favours supporting indigenous NGOs in countries like Ukraine that have been particularly badly affected by Kremlin disinformation campaigns — the UK is thought to be the only European country

building a grassroots network against false information.[12]

6.2 International Efforts Against Disinformation

In 2015 the European Union

set up a specialist Unit to report on its work monitoring pro-Kremlin disinformation. Today, EUvsDisinfo

has details of over 9,000 Russian-inspired stories it has debunked (details available on its searchable database — see Pulldown). The Wordcloud

below shows the key topics that were collected in the first half of 2017. It is clear immediately where the perpetrators' main interests lie.

More reently, the Commission

has developed a “broad-based action plan to tackle the spread and impact of online disinformation in Europe and ensure the protection of European values and democratic systems.”

The plan notes that a comprehensive policy response must reflect the specific roles of different actors (social platforms, news media & users), and define their responsibilities in terms of certain key principles, including freedom of expression, media pluralism, and the rights of citizens to diverse and reliable information.

In 2017 the Commission

set up a High Level Group

to 'advise on policy initiatives to counter fake news and the spread of disinformation online' and held consultations with citizens and stakeholders. The HLG submitted its final report

in March 2018. The following month the Commission

also published a report on ‘The digital transformation of news media and the rise of disinformation and fake news’

which presents survey data on consumer trust and perceptions of various sources of online news.

Another important agency in the fight against disinformation is the Atlantic Council. The Council runs the DFRLab

and holds regular webinars for its network of ‘Digital Sherlocks’ to share ideas and experiences — see Pulldown below.

7 Issues

Trying to keep up with the liars and malcontents who spread hatred, lies and malicious propaganda is a major concern, especially since new forms of deception continue to emerge (such as deepfake) and the bad guys seem always to be ahead of the game, and often by some margin.

The challenge of tackling the threats without degrading internet services and compromising people's privacy, security, freedom of expression and cybersecurity, is proving highly problematic.

This is

not least because of the multiplicity of agencies and organisations involved and the (all too often) poor coordination between them (because of differences in their resourcing, objectives, culture and modus operandi. There are also very real concerns about unintended consequences

(such as the chilling freedom of expression) if policies are rushed out before being properly tested.

There can be lots of excellent online fact-checkers but if people don't use them and rely instead on what they read on social media, there's a problem (which probably requires a well-designed and sustained programmes of civic education).

Big Tech may be putting a lot of effort into

trying to identify and de-list bad actors and moderate what their clients post or see, but are they up to the job, especially on platforms like WhatsApp

that are encrypted.[13]

One has to ask: does the fact that Facebook, YouTube, Twitter

and the other social media platforms are taking down more and more content indicate their success at spotting fakes, or their failure in preventing them being uploaded in the first place? Indeed, has the problem become too big to handle and does this mean regulation and curtailing their aggressive business models (designed to keep people engaged, which all to often involves nudging people to more and more extreme content). These and related issues are explored in a separate paper.

Is there anything wrong with this page?

If you would like to comment on the content, style, or the choice or use of material on this page, please use the contact form. Thank you!

Notes

1 Please note that the initiatives cited in this section are not intended as exemplars, simply interesting examples. Note also that a number of them could be put into two or more of the categories. Of course, listing an organisation or including a website link doesn't mean that Fighting Fake

necessarily endorses its views or work, but we are endeavouring to clarify which are the most important players, and will keep this section under review. We are keen to hear from anyone who can help improve this analysis / public resource.

2 Our database of initiatives and groups working to fight fake is growing fast -- we already have well over 500 listed (>100 in the UK). However, we have not attempted to establish which organisations or groups are making the biggest contributions to the fightback, individually or collectively.

3 In March 20017 Angie Hobbs (Professor of the Public Understanding of Philosophy, University of Sheffield) wrote

that young people today are constantly at risk of indoctrination from advertisers, politicians, religious extremists or the media. Here's a summary of her argument: philosophy can give young people the skills and confidence, not only to question and challenge purported facts but also to see through the current attempts in some quarters to discredit the very notions of fact, truth and expertise. It is vital that schools do all they can to help students analyse and reflect on what they hear. Good philosophical practice encourages listening skills and allows students to understand the points of view of people whose backgrounds and values may be very different from our own. Thus philosophy can help to foster empathy. And informed and well-reasoned free speech and debate among the current and future electorate is likely to improve the health of democracy.

4 “Critical thinking requires the cultivation of core intellectual virtues such as intellectual humility, perseverance, integrity, and responsibility. Nothing of real value comes easily; a rich intellectual environment — alive with curious and determined students — is possible only with critical thinking.” (Foundation for Critical Thinking)

5 Telecoms providers and Internet platforms in China are also required to aid the police with the surveillance of “crimes”, which can include actions such as calling Xi a “steamed bun” in a private chat group (punishable by two years in prison). Rupert Bear is also banned nickname, which can land people in a lot of trouble as its is considered highly disrespectful of the President. Journalist Peter Oborne set up a website to record lies and half-truths uttered by Boris Johnson: //boris-johnson-lies.com/

6 Cleanfeed, a content blocking system implemented in the UK by BT (Britain's largest Internet provider) at one stage actually blocked the Internet Watch Foundation's child abuse image content list!

7 Perhaps worth noting here that Wikipedia talks, not about ‘truth’, but about ‘verifiability’.

8 Snopes.com

was one of the first websites to validate and debunk urban legends, internet rumours and other stories of unknown or questionable origin. It is organised by topic and includes a message board where stories and pictures of questionable veracity can be posted. Storyful’s Open Newsroom

is a Google+

community where journalists and researchers are invited to help verify content, and share information. In effect it “sorts the news from the noise of the social web.” Whilst the Newsroom is open to public view, participation is moderated. Storyful’s experience is that ‘door-wide-open crowdsourcing’ often makes fact-finding harder, which is why they restrict access.

9 The high volume of ads and posts generated by bots make it difficult for fact-checkers to flag stories as misleading: the original content may have been packaged and repacked by hundreds of different accounts / websites.

10 UKRIO

was initially funded as a pilot project by a broad stakeholder group, including the UK Higher Education Funding Councils, the UK Departments of Health, the Research Councils, the Royal Society, research charities and a variety of other organisations. It is now "expanding the pool of funders, and seeking support from universities, NHS

organisations the Department of Health, other Government Departments and research organisations such as public and private sector research institutes and industry."

11 Here's an extract from the Executive Summary: "There are fears that democratic institutions and national elections are under threat from mis-, dis-, and mal-information shared on a huge scale online and on social media platforms. Mob lynchings and other violence based on false rumours have turned fake news into an emergency in some parts of the world, costing lives and causing significant problems for societies. This has prompted a number of governments to adopt measures ranging from legislative and legal action to media literacy and public awareness campaigns to fight the spread of disinformation. In addition, international pressure on tech and social media giants has been increasing to urgently address the spread of disinformation on their platforms or face the possibility of fines or regulation. However, rights groups have also argued that the fight against disinformation and fake news has been used to make unjustified arrests or pass repressive laws that primarily aim to silence political dissent and limit freedom of speech and expression."

12 For the record: GCHQ

has a ‘dirty tricks’ unit, the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group

(whose existence was exposed by Edward Snowdon in 2014); the British Army

has a psychological warfare unit, the 77th Brigade, and is reconfiguring its 6th Division

to fight cyber threats and seek to influence the behaviour of the public and adversaries by specialising in ‘information warfare’.

Mystery surrounds the work of the London-based Institute for Statecraft

which was founded in 2009 with the stated mission of defending democracy from disinformation, and in particular from Russia. The Institute's object is “to advance education in the fields of governance and statecraft, and to advance human rights.” In late 2018, Russian media asserted that Anonymous

(the international hacktivist group) released documents about the Institute's Integrity Initiative, which purported to show the programme was part of a disinformation project to interfere in other countries. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office

blamed Russia for the release, which were said to be "intended to confuse audiences and discredit an organisation which is working independently to tackle the threat of disinformation". The National Cyber Security Centre

launched an inquiry into possible computer security breaches at the Institute. At the time of writing "All content on the Institute’s website has been temporarily removed, pending an investigation into the theft of data from the Institute for Statecraft and its programme, the Integrity Initiative."

13 Encryption means platforms (and governments) can’t check content, but they can monitor suspicious or inauthentic behaviour (eg rate and number of posting, time of day, etc...)