Recommendations

This page highlights the recommendations made in selected reports published in the last few years and where appropriate the principles that underlie them. It is important to understand the context in which these recommendations were made, so please consult the reports (which are available online) — and most importantly, read the fine print!

Page Content

Reports Featured

It is a hopeless task trying to keep abreast of all the books and reports

now being published that make recommendations for tackling the multitude of problems associated with protecting freespeech and the mainstream media, and with internet governance, 'fake news' and disinformation.

I have brought together some of the best proposals on the Battle for Truth Page. The purpose of this page is to provide more information on some of the key underlying documents.

I'll try to keep to just four reports per category...

1 The Online World

The mission of the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace* is "to develop proposals for norms and policies to enhance international security and stability and guide responsible state and non-state behavior in cyberspace." The Commission

helps to "promote mutual awareness and understanding among the various cyberspace communities working on issues related to international cybersecurity."

The Commission's Final Report offers "a cyberstability framework, principles, norms of behavior, and recommendations for the international community and wider ecosystem."

* The Commission was launched at the 2017 Munich Security Conference.

The Commission's Final Report offers "a cyberstability framework, principles, norms of behavior, and recommendations for the international community and wider ecosystem."

* The Commission was launched at the 2017 Munich Security Conference.

The Commission

notes that while some continue to believe that "ensuring international security and stability is almost exclusively the responsibility of states," in practice "the cyber battlefield (i.e., cyberspace) is designed, deployed, and operated primarily by non-state actors" and "their participation is therefore necessary to ensure the stability of cyberspace."

It concludes that these non-state actors should be guided by some basic principles and bound by norms, and argues that: 1) Everyone is responsible for ensuring the stability of cyberspace; 2) No state or non-state actor should take actions that impair the stability of cyberspace; 3) State or non-state actors should take reasonable and appropriate steps to ensure the stability of cyberspace; and 4) Efforts to ensure the stability of cyberspace must respect human rights and the rule of law. The Commission

goes on to make six recommendations focus around "strengthening the multistakeholder model, promoting norms adoption and implementation, and ensuring that those who violate norms are held accountable." [See pulldowns]

"The Web was designed to bring people together and make knowledge freely available. It has changed the world for good and improved the lives of billions. Yet, many people are still unable to access its benefits and, for others, the Web comes with too many unacceptable costs." The Contract for the Web

is "a global plan of action to make our online world safe and empowering for everyone", with the Contract created by representatives from over 80 organizations, representing governments, companies and civil society, and sets out commitments to guide digital policy agendas. To achieve the Contract’s goals, "governments, companies, civil society and individuals must commit to sustained policy development, advocacy, and implementation of the Contract text."

The pulldowns below contain the main proposals, but do read the original for clarification and examples of things that can / should be done.

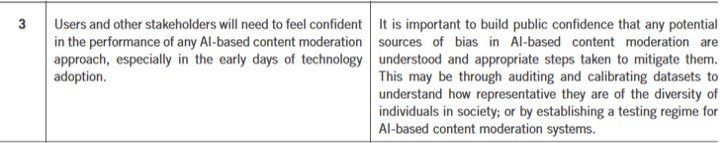

'The Age of Digital Interdependence' was prepared by a High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation

convened by the UN Secretary-General

to "advance global multi-stakeholder dialogue on how we can work better together to realize the potential of digital technologies for advancing human well-being while mitigating the risks."

The report

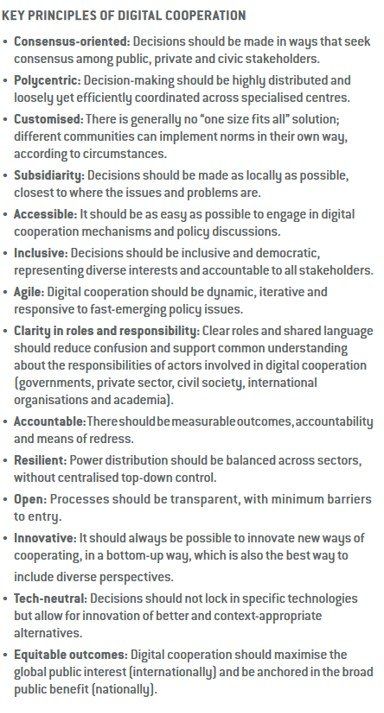

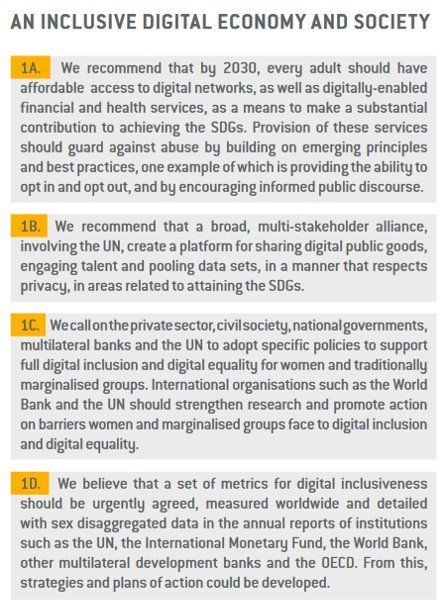

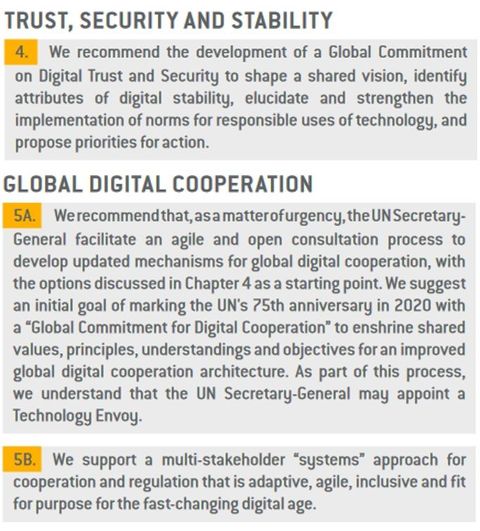

argues that "our rapidly changing and interdependent digital world urgently needs improved digital cooperation founded on common human values". It makes 11 main recommendations which are grouped under the following headings: 1) Build an inclusive digital economy and society; 2) Develop human and institutional capacity; 3) Protect human rights and human agency; 4) Promote digital trust, security and stability; and 5) Foster global digital cooperation.

The recommendations are listed below together with some key principles of cooperation.

The Global Commission on Internet Governance

provides recommendations and practical advice on the future of the Internet. Its primary objective is the creation of 'One Internet' that is protected, accessible to all and trusted by everyone. In its final report, the Commission

"puts forward key steps that everyone needs to take to achieve an open, secure, trustworthy and inclusive Internet." As is says: "Half of the world’s population now uses the Internet to connect, communicate and interact. But basic access to the Internet is under threat, the technology that underpins it is increasingly unstable and a growing number of people don’t trust it to be secure."

The statement (in the pulldown below) provides the Commission’s view of the issues at stake and describes in greater detail the core elements that are essential to achieving a social compact for digital privacy and security.

2 The Information Crisis

In Nov 2020, the Forum on Information and Democracy

published a report

prepared by its Working Group on Infodemics. The work is based on more than 100 contributions from experts, academics and jurists from all over the world and "offers 250 recommendations on how to rein in a phenomenon [the infodemic*] that threatens democracies and human rights, including the right to health."

* An infodemic is an overload of information, often false or unverified, about a problem, especially during major crisis.

Main Recommentations

The Transparency Paradox

"What could be perceived as a transparency paradox

arises, as on the one hand greater access to information and metadata is recommended, while on the other an attempt must be made to prevent future damaging misuse of data, such as in the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Differential privacy

could allow a safe approach to transparency. ‘Differential privacy’ describes a promise, made by a data holder, or curator, to a data subject: ‘You will not be affected, adversely or otherwise, by allowing your data to be used in any study or analysis, no matter what other studies, data sets, or information sources, are available.’ At their best, differentially private database mechanisms can make confidential data widely available for accurate data analysis, without resorting to data clean rooms, data usage agreements, data protection plans, or restricted views.... Differential privacy addresses the paradox of learning nothing about an individual while learning useful information about a population." [p22]

This report

identifies policy options available for the European Commission

and EU

member states should they wish to "create a more enabling environment for independent professional journalism... Many of these options are relevant far beyond Europe and demonstrate what democratic digital media policy could look like." The authors argue that to thrive "independent professional journalism needs freedom, funding, and a future. To enable this, media policy needs: a) to protect journalists and media from threats to their independence and to freedom of expression; b) to provide a level playing field and support for a sustainable business of news; and c) to be oriented towards the digital, mobile, and platform dominated future that people are demonstrably embracing – not towards defending the broadcast and print-dominated past."

The report "identifies a number of real policy choices that elected officials can pursue, at both the European level and at the member state level, all of which have the potential to make a meaningful difference and help create a more enabling environment for independent professional journalism across the continent while minimising the room for political interference with the media." In particular, it explores

four important areas of traditional and new media policy where policymakers have options available that can help create a more enabling environment for independent professional journalism:

1. Free expression and media freedom;

2. Disinformation and online harms;

3. Competition and data protection;

4. News media policy.

After detailing the main problems associated with these four areas, the report makes a number of policy suggestions (listed in the pulldowns below):

The report

of the LSE's Truth, Trust & Technology Commission

makes an important contribution to the debate. The Commission

spent more than a year addressing questions such as 'How should we reduce the amount of misinformation?’ 'How can we protect democracy from digital damage?’ and 'How can we help people make the most of the extraordinary opportunities of the Internet while avoiding the harm it can cause?’

The Commission

identifies 'Five Giant Evils of the Information Crisis' (shown below) and recommends the formation of an Independent Platform Agency

(IPA), a watchdog which would evaluate the effectiveness of platform self-regulation and the development of quality journalism, reporting to Parliament and offering policy advice.

IPA should be funded by a new levy on UK social media and search advertising revenue. It should be "a permanent forum for monitoring and reviewing the behaviour of online platforms and provide annual reviews of ‘the state of disinformation’. In addition to it’s key recommendation the Commission

also proposes a new programme of media literacy and a statutory code for political advertising."

"The UK and devolved governments should introduce a new levy on UK social media and search advertising revenue, a proportion of which would be ring-fenced to fund a new Agency [which] should be structurally independent of government but report to Parliament."

The IPA's initial purpose will be "not direct regulation, but rather an ‘observatory and policy advice’ function, and a permanent institutional presence to encourage the various initiatives attempting to address problems of information." It should be established by legislation and report on trends in online news and information sharing and the effectiveness of self-regulation. In addition:

• Government should mobilise and coordinate an integrated new programme in media literacy.

• Legislative change is needed to regulate political advertising.

3 Tackling Threats Posed by AI

‘Fake news’ and disinformation are today being facilitated by social media with the aid of artificial intelligence [AI] and machine learning [ML]

In late 2018 researchers succeeded in using ML to generate highly realistic fake images and videos known as 'deepfakes.' Artists, pranksters and others (including hostile foeign powers) have subsequently used these techniques to create a growing collection of audio and video depicting high-profile leaders, such as Donald Trump, Barack Obama, and Vladimir Putin, saying things they never said. This trend has driven fears within the national security community that recent advances in ML will enhance the effectiveness of malicious media manipulation efforts like those deployed during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

This paper

examines the technical literature on deepfakes to assess the threat they pose. It draws two conclusions. First, the malicious use of crudely generated deepfakes will become easier with time as the technology commodifies. That said, the current state of deepfake detection suggests that such fakes can be "kept largely at bay". Second, tailored deepfakes produced by technically sophisticated actors will represent the greater threat over time. Even moderately resourced campaigns can access the requisite ingredients for generating a custom deepfake. However, factors such as the need to avoid attribution, the time needed to train an ML model, and the availability of data will constrain how sophisticated actors use tailored deepfakes in practice."

Edited versions of the report's four main recommendations are provided in the pulldowns below:

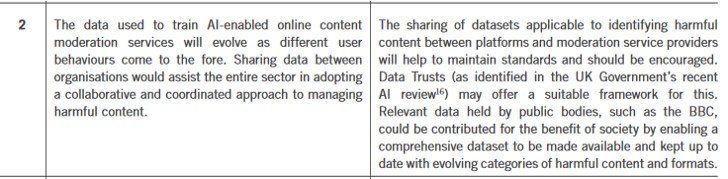

"In recent years a wide-ranging, global debate has emerged around the risks faced by internet users, with a specific focus on protecting users from harmful content. A key element of this debate has centred on the role and capabilities of automated approaches (driven by AI & ML techniques) to enhance the effectiveness of online content moderation and offer users greater protection from potentially harmful material."

"These approaches may have implications for people’s future use of — and attitudes towards — online communications services, and may be applicable more broadly to developing new techniques for moderating and cataloguing content in the broadcast and audiovisual media industries, as well as back-office support functions in the telecoms, media and postal sectors."

This report

— penned by Cambridge Consultants

and commissioned by Ofcom

— highlights four potential policy implications:

Context

Policy Implications